You can download the Architecture Design Competitions - A Guide for Government here or find the full text below.

Competitions assure the optimisation of the decision-making process. They create a formal framework with clear deadlines and assist in the search for the best possible solution.

Purpose

This document provides guidance and advice to government organisations on how to enable high-quality design outcomes through architecture design competitions. It helps government organisations get the most out of using a competition as a procurement method.

About architecture design competitions

Architectural competitions are a breeding ground for new ideas and new talent, they smash preconceptions, break down barriers and produce award winning designs.

Architecture design competitions offer government an alternative way to seek high-quality design as the major selection criteria for a project. With an appropriate budget in place, competitions can generate excellent outcomes for clients and a quality built legacy. Architectural design competitions help to open up the field of participants, generating public interest in the project and supporting innovation. Investing time to fully prepare for a competition and especially developing the competition design brief, will attract a much broader range of quality entries.

Architecture design competitions are an effective opportunity for developing professional skills within government by inviting senior managers and decision makers to participate in the process, build their capacity and broaden their knowledge. Competitions can help test assumptions, broaden outlook and maximise opportunities prior to implementing built work.

Architecture design competitions allow government to compare a variety of building forms, spatial configurations and construction technologies with the support of relevant experts. The advantage of using a competition is the implementation of a professional process, where there is the opportunity to engage stakeholders, mitigate risk, generate new research, enhance design awareness, reduce timelines and create internal capacity for the future.

There are different types of design competitions that vary in their scope and application. Decisions about which competition process to use will depend on the size, objectives, time constraints and design flexibility of the project. Key participants include the client group, project reference group, jury, probity adviser, legal adviser and competition adviser.

The Office of Victorian Government Architect (OVGA) assists by advising on the characteristics and virtues of each form of competition.

Historically competitions have been a regular and successful method for procuring significant projects. Today many European countries such as Belgium, Denmark, Switzerland, France and Germany require or encourage projects over a certain size – especially public projects – to be procured through design competition. In places where there is a strong design culture, competitions are the norm and help to create quality architecture and improve the built environment, while leading to the export of design services internationally.

Design competitions have been successfully used in many projects across Australia, however they are yet to be fully embraced as a more standard form of procurement.

In recent years, OVGA has been approached by many regional councils and state agencies to provide advice on how to run an architectural design competition and to be part of the jury. As a consequence OVGA has prepared this document to help government organisations realise the benefits of, and to prepare for, an architectural design competition.

When to use an architecture design competition

Architecture design competitions are appropriate when:

- The project is of public significance.

- The process will benefit from the public interest that a competition can generate.

- Seeking new ideas, innovation and design excellence is a high priority.

- A project will benefit from a wide design analysis.

- The client is able to provide a clear and unambiguous brief.

- The project is on a significant or unusual site.

- The budget is derived from satisfactory benchmarking and can meet the design ambitions of the competition process, and those funds are available for the project to proceed.

How competitions strengthen the design industry and the community

A strong architectural design industry is a great benefit to a growing economy. Economic growth impacts bricks and mortar as much as it impacts the stock exchange and interest rates. It is not a coincidence that Europe has a strong architecture sector, which exports services around the world. When government encourages and promotes the profession of architecture, it benefits from the potential to offer this as an export service. Competitions can support Victoria to be an acknowledged ‘design state’, and as a means to export Victorian architectural design services internationally by providing an entrepreneurial environment.

The advantages of a competition

An architectural competition has a number of advantages by allowing the design of a new project to commence before the architect is even commissioned, helping to effectively reduce time, risk and cost.

The benefits of a competition are that it:

- Allows a client to engage in a professional process to achieve a positive outcome.

- Focuses a client to fully understand what they require through the preparation of a brief.

- Allows for early scoping and testing of ideas in response to the brief.

- Assists a client to champion design quality from the start.

- Allows focus on the big issues of a project rather than barriers or premature detail.

- Offers evidence of expertise and diverse design approaches by a broad range of architects and design teams prior to selection.

- Provides a focus for new knowledge to be tested.

- Facilitates a vision that will help capture public support.

How competitions engage stakeholders

Well-prepared architecture competitions allow all stakeholders to express their expectations and views on a project. Most project sites have numerous stakeholders from across the public and private sectors. Design competitions can reduce risk and avoid conflict by providing a non-confrontational forum where views can be openly expressed, debated and resolved from very early in the process.

Architectural competitions allow stakeholders to add valuable insights regarding developing the brief, understanding context, historical associations, reviewing entries and providing comment, within a professional and independent framework. The independence of a well-run competition can mitigate political risk, unify disparate stakeholders, resolve conflict and realise the potential of a project.

Architectural competitions help to create a positive awareness and generate market interest before the procurement details are fully decided. Through informed consultation and intelligent planning, competitions help to promote a design concept and elevate the profile of a project.

International participation

For large projects, it may be considered appropriate to open the competition to international participation. This can widen the range of architectural input and promote collaboration between global and local practices. An international perspective may also elevate the value of the competition to facilitate new international networks and learnings.

Anonymity

In a two-stage architectural competition, the first stage is usually anonymous. This means that entries are lodged without the author being revealed to the jury. In this way, all entries are viewed equally by the jury and are selected on the merits of the design ideas presented, rather than any other criteria and without any bias towards known architects. This is especially important where there is a desire to unearth unknown talent.

In a two-stage process, a capability assessment would be included in stage 2, where any less experienced entrants have the opportunity to collaborate with another practice or increase their team with more experienced members.

Requirements of the process

A successful architectural competition hinges on a number of important interrelated factors: a supportive client, a well-researched and well-written brief, and a professionally run process.

The two key documents are the competition brief and the competition conditions. The competition brief contains all information related to the design of the project, while the competition conditions detail everything else, including competition format, timeframe, jury, eligibility, anonymity and everything else related to the running of the competition.

The following are important points to consider for the preparation of a successful competition.

Competition Communications

Communication is one of the most important factors in the running of a successful architectural competition. All information for and about the competition needs to be clear and concise, intelligent and informative, so it can be understood by the widest possible audience. A competition adviser will assist a client to gather and disseminate information about the competition.

Communicating with the profession

The competition brief should clearly outline the physical requirements of the project related to brief, budget, timeframe, procurement methods and any other important factors related to the design of the project, while the competition conditions should clearly state the competition process, client, timeline, remuneration, jury and any other important factors related to the running of the competition.

Communicating with client, government and stakeholders

The competition brief and conditions will give the client, government and stakeholders the opportunity to reflect on the true requirements of the project and clarify what is most important for the design of the project.

Communicating with the public

The communications around the architectural competition should be positive and inclusive of the needs of the community.

Competitions take us to places we never expected to be. We don’t know where we might end up, but it won’t be where we intended, and that really gets us thinking.

The competition brief

A well-prepared and clearly written competition brief underpins a successful architecture competition. It captures the client’s aspirations for the proposed project and sets the foundation for the procurement process. The preparation of the competition brief is an opportunity to gain stakeholder input to ensure the design can respond to any competing demands. A good brief shows a clear understanding of the context and planning controls and communicates the key opportunities and constraints. Most entrants will not personally visit the site, so the brief and the statement of purpose must be clearly written and contain all the information required to design a successful project.

A good brief clearly explains the design intent, but also details the functional requirements. This includes space requirements, budget outline and important planning constraints. You should allow flexibility for entrants to extrapolate and laterally explore ideas that may not immediately be apparent. It is important to clarify details of the client, site, the budget (construction and overall), project timeframe, procurement method and any other important factors that will impact upon the design.

Every piece of information contained in the competition brief should send a clear message to potential entrants about the issues that are most important to the client.

The competition conditions

The second component of the competition documents sets out the governance of the competition, detailing the type of competition, key participants and all terms and conditions of the competition. It includes:

- The format of the competition.

- Whether the competition is anonymous.

- Timeline and deadlines.

- List of deliverables/required content.

- Jury composition, with details of each jury member.

- The assessment criteria, including selection criteria and weighting apportioned to design. The assessment criteria and weighting must be defined together by the client and the competition adviser (see key participants section).

- Details of the competition adviser.

- Communications intent (through exhibition or publication).

- Prize money details.

- Whether or not a commission will be offered to the winner.

Further detail in the competition conditions will include an explanation of the following terms:

Eligibility

Any restrictions on eligibility should be advised clearly. A condition of Australian Institute of Architects (AIA) endorsement requires all entrants to be registered architects. Team entries must list member names, to avoid complex intellectual property claims. Eligibility may include past experience requirements similar to expression of interest processes.

Non-eligibility

Associates, employees or direct family of the client, jurors or the adviser are not eligible to compete.

Disqualification or non-compliance

The competition must clearly identify the circumstance under which a competitor may be disqualified or deemed non-compliant, typically through not adhering to one or more conditions of entry.

Conflict of interest

Entrants must disclose any conflicts of interest.

Confidentiality

Often entrants receive information of a confidential nature, which the competition must clearly identify and require confirmation of all entrants through a simple non-disclosure agreement.

Propriety

Conditions should include a clause about not contacting representatives of the client or members of the jury.

Correspondence protocols

These should state who to contact, by what means and over what period.

Copyright and moral rights

In most circumstances, prospective entrants will not enter a competition unless they are confident their intellectual property rights will be protected. Unfortunately, there have been occasions where unscrupulous sponsors have disregarded entrants’ copyright or moral rights.

Architecture competition conditions must state clearly that entrants retain copyright to their entries. The client may make certain uses of the entries for archival, communications and publicity purposes. Where other uses are known, these uses should be stated in the competition conditions. Entrants will be required to clearly define their requirements for attribution of their work in the competition and undertake that the attribution requested is agreed to by all holders of moral rights in the design.

Lodgement requirements

Improper lodgement may lead to disqualification, so clear protocols regarding where, how and when to lodge entries are essential. Lodgement increasingly takes the form of digital files and uploads, however this is not always appropriate. Above all, lodgement requirements must deliver consistency across all entries, to allow balanced and fair assessment by the jury.

Appendices

A good competition will deliver everything the design team needs to understand the brief, the site and the planning provisions. These additional documents may be contained within appendices. Documents might include local or state urban design strategies that impact the subject site, previous reports including site surveying or geotechnical engineering, nearby transport and infrastructure resources and relevant heritage and conservation provisions that affect the subject site.

Legal Advice

Formal legal advice may be required before proceeding with the public dissemination of the competition brief and conditions.

Jury report

The final key document for a competition is compiled at the conclusion of the judging process, where the jury, usually assisted by the competition adviser, writes a report explaining its decisions.

The jury report provides:

- Written evidence to entrants, the client and the public that the evaluation and selection procedures were executed in a professional, impartial and informed manner.

- An insightful document for the client, the public and the architecture profession that describes the judging process and the criteria for evaluating the designs.

- A historic record of the competition detailing the winner (and any finalists), explaining why their designs were chosen.

Key participants

The client

A good client will understand and appreciate the value of an architecture design competition and will decide that a competition is the most appropriate form of procurement based on the project requirements and expert design advice.

Once it has been determined that a competition is appropriate, the client will engage a professional competition adviser to assist with all matters related to the successful preparation and running of the architecture design competition. With the competition adviser’s input, the client will then select the appropriate competition type, develop the brief and assemble the background documents, including the project vision, exemplar images, a clear and well-laid out format and a tested budget.

The client will also assist with strategic stakeholder engagement, marketing and communications.

Competition adviser

The competition adviser is a professional consultant (often an architect) engaged by the client, whose role is a vital bridge between the client, the jury and the entrants. In most cases, the competition adviser advises the client on all matters relating to the architecture design competition. It is the competition adviser’s role to guide the client through each key decision, from competition format, to jury selection, judging criteria, timing, eligibility, prize money and all matters related to the successful preparation and running of the architecture competition. The competition adviser should remain impartial throughout the competition process.

The entrants

A well-prepared architecture design competition will attract the best designers, either locally or internationally if the correct steps are in place. Entrants need to see the value in the process, feel confident that the project is clearly defined, that probity safeguards are in place, due process will be followed and that their intellectual property and moral rights will be protected.

If the competition is a real project, it is critical that the entrants are given confidence the winning team will be engaged to deliver the project despite any change in government.

Project reference group

Depending on the type of project, a project reference group may be formed to oversee the competition process, provide feedback, and/or be champions of the project. The project reference group can ensure that the competition processes are properly established and followed.

Probity adviser

The client may choose to appoint a probity adviser to manage risk, oversee and advise on all decisions made by the jury and competition adviser.

Legal adviser

A legal advisor has a small but vital role in helping to define and interpret the wording used throughout the competition brief and conditions. The legal adviser may also provide support if unforeseeable problems arise during the competition.

Registrar

The client may choose to appoint a registrar to receive entries. Where anonymity is required, only the registrar should be aware of the identity of entrants and will prepare the presentation material prior to the jury meeting. This role may also be filled by the competition adviser.

Jury

The jury should include a mix of people with specialist skills and knowledge from the public and private sector. The composition of the jury is important, as it plays a significant role in generating interest and participation from the widest possible cross-section of entrants.

The jury must engender the respect of the design community and confidence as to their expertise. In order to judge design merit, the jury should comprise a majority of architects and landscape architects. The selection, quality and status of the jury will inform not only the outcome, but also attract and enhance the breadth of entries. The jury must be professional, impartial, knowledgeable and able to commit sufficient time and energy to the deliberation process.

To perform effectively the jury members should:

- visit the project site

- read and understand the competition brief and conditions

- view all the entries in a fair and equitable way without interference from any outside influences

- have an appropriate space in which to deliberate

- prepare a qualified report explaining its choices

- maintain confidentiality as required

- reach a unanimous or majority decision (whichever is required by the competition conditions)

- be appropriately remunerated for their time, including travel and accommodation costs

Generally, all jury members should give their assurance they will be available for the entire competition process before they are selected.

It is appropriate to aim for uneven numbers on the jury to be able to achieve a majority decision if a unanimous decision cannot be reached. Where a jury has equal numbers, it would be appropriate to specify that the deciding vote sits with the chair.

Jury chair

The jury chair formally convenes the jury and is responsible for leading the assessment process in accordance with the competition brief and conditions. The jury chair’s role becomes particularly important if the jury’s decision is split or conflicting. The jury chair’s ability to negotiate disagreement and explore acceptable compromises is essential to reach a positive conclusion.

Australian Institute of Architects

To ensure that government aspires to best practice and a fair and equitable competition process, it should seek endorsement from the Australian Institute of Architects (AIA). The AIA is the representative body of the architectural profession and has a policy that helps to secure the best possible participation from the profession.

Endorsement of an architectural competition by the Australian Institute of Architects can significantly enhance an architectural competition because it can:

- Increase the number and quality of entrants.

- Offer effective, targeted promotion of the competition to AIA members.

- Give all participants in the competition (entrants, sponsor, client, jury and advisers) assurance about the fairness and equity of the competition.

- Assist in protecting the rights of entrants.

- Include advice to the competition adviser and thus assure the client, sponsor and entrants that the competition will be well run.

- Reduce the risk of negative publicity.

AIA endorsement is given for an architectural competition that complies with the AIA’s Architectural competitions policy in at least the following provisions:

- All entrants are treated equitably.

- All entries are anonymous (where applicable).

- Entry deliverables are reasonable and aimed at a minimum to allow informed design judgement.

- Conflict of interest is prohibited.

- Fee proposals are separate and limited to a prescribed range, or the proposed fees are clearly stated in the competition documents.

- The author of the winning design is to be engaged as the project architect (where appropriate).

- Prize money and fee amounts are listed and specified to be paid within a reasonable time.

- A majority of entrants are Australian-based.

- Intellectual property and moral rights of entrants are protected.

- The AIA is notified of any material change to competition conditions or process.

- The AIA is provided with a copy of the final jury report at the conclusion of the competition.

One of the more challenging aspects in the conduct of an architectural competition is establishing fair, equitable and appropriate rules. The AIA policy document Model conditions for an architectural competition provides a template set of rules that can be easily adapted, as required, for most typical competitions. Using the model conditions as the basis of an architectural competition assists in ensuring a high level of compliance with the policy, and thus an easier pathway to AIA endorsement.

The Australian Institute of Landscape Architects also provides direction with their Guidelines for the promotion and conduct of competitions.

Competition types

There are many types of architecture competition. An architecture competition may be considered as a way of uncovering creative architectural ideas that would not be found through the usual engagement processes.

The type of competition will vary, depending on the objectives of the client, however this document outlines four of the most appropriate competition types within the two broader categories of project competitions or ideas competitions.

The two broad categories are project competitions and ideas competitions.

A project competition leads directly to the construction of a specific project on a specific site or sites. The objective of such a competition is to select the design that best responds to a clearly defined project brief. The author of the winning design is subsequently engaged to develop the design and complete the project (subject to reasonable conditions) and demonstration of capability and capacity.

An ideas competition does not lead directly to engagement of the winner to realise their winning design. It is used to explore major design issues or design opportunities, generally for a significant site. Because there is no expectation for the client to commission the competition winner, ideas competitions are generally more risk-free environments that encourage wide-ranging solutions and innovative design strategies.

An ideas competition is not appropriate where it:

- only promotes or advances a private or commercial interest

- does not benefit either the public or the profession

- is not explicit about its purpose

- there is no remuneration

Competition types fall into one of the following four categories:

Open competition

Open competitions permit the broadest range of architects to enter and give all entrants an equal opportunity to be selected, based predominantly on design merit, rather than on proven capability or prior experience. This format is appropriate where the project requires the widest exploration of potential solutions. It is also appropriate where the client desires to uncover talented architects who may not yet have had the opportunity to design a particular type of project. There is an expectation that on awarding a winner, the competition will lead directly to the construction of a specific project on a specific site, subject to demonstration of methods to achieve capability and capacity.

Limited (open) competition

Limited (open) competitions are still open to a wide range of architects, but entry may be restricted according to specific factors such as where the architect resides, budget restrictions, or specialist design knowledge requirements. This format includes the requirement to meet certain minimum standards, which will be assessed independently of design entries. There is an expectation that on awarding a winner, the competition will lead directly to the construction of a specific project on a specific site, subject to demonstration of methods to achieve capability and capacity.

Limited (select) competition

A limited (select) competition limits eligibility to a specific cohort but entrants are selected by the client based on defined selection criteria. The selection criteria may be purely qualification based, or may require an initial, broad conceptual design response to the brief. There is an expectation that on awarding a winner, the competition will lead directly to the construction of a specific project on a specific site, subject to demonstration of methods to achieve capability and capacity.

Select competition

A select competition limits eligibility to a small group of entrants selected directly by the client. The architects are paid a fee to cover the costs of their work. Often, select competitions are preceded by an expression of interest, which allows the competition proponent to review a selection of suitable candidates based purely on prior achievements. From the list of expressions of interest received, the client can invite a limited number of architects to enter design proposals. Typically, this reduces the process to a single-stage competition.

Costs of running a competition

The average total costs of a competition amount to 0.5–1.5 per cent of the construction sum, and for major projects they are significantly lower. The intense consideration of the task and the multitude of proposed solutions do often reveal new aspects that are relevant for the sponsor.

An architecture competition may include the following costs, in addition to other project costs and consultants’ fees, including:

- Client’s direct and indirect costs, including staff and travel costs.

- Advisers’ fees, expenses and administrative support costs.

- Jury and technical panel fees, honoraria and expenses and all costs associated with meetings of the jury.

- Costs of acquiring and documenting relevant site information, including a site model if appropriate.

- Exhibition costs, whether physical or online.

- Media, public relations and publications costs (including preparation and graphic design for the competition brief and conditions), before, during and after the competition.

- Prize money and fees.

The amount of prize money must relate to the size and complexity of the project, the amount of work required by entrants, the likely costs of preparing a compliant entry, whether the entrants are also paid a fee and the nature of any post-competition commission.

Entrants should be able to expect that, if they win, they will recover all the costs of entry preparation plus a premium as reward for winning. If they are placed second or third, they will expect to recover at least 50 per cent of the cost of entry preparation. Unplaced entrants will generally accept the cost risk of participation, provided they are not expected to undertake unreasonable amounts of work.

A fair and reasonable procurement process will ensure that competition payments and prize money will be separate from any professional fees payable as part of the subsequent commission that arises for the competition winner. The notion that the competition process and outcome somehow gives the commissioned architect a ‘head start’ is a common misconception. In reality, much of the work done by the winner during the competition will have to be redone or revalidated, and the brief will also need to be substantially revisited.

Architectural fee proposal

If a fee proposal is required as part of the competition entry, the client and a suitably qualified quantity surveyor must pre-determine a reasonable range (based on the stated budget) within which the fee would be considered acceptable based on industry standards. Each entrant’s fee proposal should be:

- lodged under separate cover

- opened only after the preferred design is determined

- accepted if it falls within the pre-determined range

- subject to negotiation with the author of the preferred design if it is not within the pre-determined range

If fee negotiations with the preferred entrant are unable to deliver an agreed outcome, the above process can be repeated with the author of the second preferred concept. If successful, that entrant may then be declared the winner. If this method is to be considered, it should be stated in the competition conditions before the competition commences.

Actions for design-led procurement

In summary, to encourage design-led procurement OVGA recommends that architecture design competitions:

- Appoint a professional competition advisor to assist in the process and offer impartiality and confidentiality.

- Ensure that the competition adviser and brief writer (often the same person) set out the competition process and the rules to avoid false assumptions. This helps to support a balance between risk and reward for the profession.

- Allow adequate time to plan, organise, manage and judge the competition.

- Allow appropriate time for entrants to undertake the necessary design work.

- Appoint a jury that includes a mix of professional and respected specialists that will generate a broad level of interest and engender the respect of the architectural design profession and the broader community.

- Provide a set of clear, unambiguous and well-laid out competition documents that provide relevant background material, the vision and rules for the competition and good design precedents.

- Engage other stakeholders to review the brief.

- Identify and be clear about the proposed method for delivery of the built project.

- Use the right tone to inspire entrants to deliver the vision.

- Familiarise entrants with the site by ensuring the context is explained and allow for a site visit (where appropriate).

- Establish and publish the criteria by which the entries will be judged.

- Establish a reasonable budget and construction program that accurately reflects the brief.

- Offer sufficient prize money to attract entrants.

- Protect the intellectual property and the moral rights of the architects.

- Pay entrants a fee for work in a second stage.

- Engage the winning team to deliver the project, if the project is to proceed.

Any competition is only as good as the way it is run, as good as the people organising it, writing the brief, selecting the people to judge it and the process for judging it. And it is here that standards vary. Sometimes they are fantastic ... and sometimes they are a little suspect.

Case studies

Competition case study 1

Project name: Flinders Street Station Competition

Winning designers: Hassell / Herzog & De Meuron / Purcell UK / Arup

Competition Type: Ideas Competition

Year: 2012–2013

Location: Flinders Street Station, Melbourne

Client: Major Projects Victoria

Endorsement: Australian Institute of Architects

Process

The State Government of Victoria sponsored a $1 million, international design competition for Flinders Street Station in 2012, with the winner announced in 2013. The competition sought ‘innovative design proposals to invigorate the historic Flinders Street Station, improve its transport function and unlock the urban design and development potential of the precinct’.1 The station is one of Australia’s most important heritage sites and one of the nation’s busiest train stations, ensuring that the competition attracted both national and international interest.

Major Projects Victoria managed the process and established a comprehensive governance framework with a project steering group, design brief panel, jury and design competition adviser. Each group had clearly defined roles and responsibilities. Government departments across state government (including the Office of the Victorian Government Architect) were represented in these groups and worked collaboratively to develop a comprehensive design brief for the competition. The Victorian Government Architect Geoffrey London chaired the jury.

The competition process endorsed by the Australian Institute of Architects, was a two-stage process. Stage one was anonymous, and invited architectural teams to enter up to three presentation boards inclusive of drawings, diagrams and written statements outlining the vision, principles and an outline of approach. Six entries were shortlisted for stage two, and paid a $50,000 fee for the second stage.

Stage two required the shortlisted proponents to develop their initial concept design based on stage one jury comments and interactive sessions with the design brief panel. The proponents then presented their respective designs in detail and responded to questions from the jury. The second stage requirements included the preparation of six presentation boards including drawings (1:1000 masterplan; 1:200 plans, elevations and sections), text, a 3D model and a two-minute animation.

Outcome

The design competition was won by a global collaboration comprising the architectural firms Hassell (Australia) and Herzog & De Meuron (Switzerland); heritage consultants Purcell (UK) and engineers Arup. The winning design transformed the station into a public place – a civic destination with a distinct architectural identity and a home for many different activities to complement the transport function of the station. It was judged by the jury to be a ‘beautiful and compelling integration of aspects of the original station design, strongly reinforcing its gateway status.’2

Following the design competition, Hassell worked with Major Projects Victoria on a preliminary business case for state government funding through the Department of Treasury’s gateway process for high-value high-risk projects. The project did not go ahead as conceived in the competition. In 2015, Hassell were contracted to undertake concept design for the $7 million upgrade of the station.

The process was unique at the time in that the Victorian public was also provided with an opportunity to vote and provide feedback on the shortlisted designs in the form of a People’s Choice Award. The public was able to view the shortlisted designs online, and was asked to consider the same evaluation criteria that the jury used to guide their decision-making process including: overall design merit, transport function, cultural heritage and iconic status and urban design and precinct integration.

The winning design and People’s Choice Award were both announced in August 2013.

Key Initiatives to protect design quality

- There was a comprehensive and visually compelling design brief, including well-considered evaluation criteria that could be used by entrants, jury and public alike.

- The client retained a commitment to the design quality and intent of the project and the process.

- A design competition adviser and strong representation from the Office of the Victorian Government Architect throughout the process assisted the client and signalled the importance and value that government was placing on design quality.

- The Australian Institute of Architects endorsed the competition guidelines, and a design competition adviser was appointed. The client followed the recommended and endorsed design competition processes with which all designers were familiar.

- The process of shortlisting and provision of payments to each of the shortlisted entrants recognised the value of the design teams’ input.

- The use of oral presentations assisted in focusing the client selection process and identifying the design teams’ capacity to work with client and stakeholders.

- The management of the project by Major Projects Victoria with strong leadership and support from the Office of the Victorian Government Architect showed the importance and value of design quality.

- The strong governance structure meant that each group had defined roles and responsibilities. The government departments represented in these groups often had different requirements and priorities for Flinders Street Station, however they worked collaboratively together to achieve the required outcome. Each department or entity was able to represent their respective needs during the development of the design brief, one-on-one sessions and technical design review.

- The publicity surrounding the opening of the People’s Choice Award voting and the announcement of both the Jury winner and People’s Choice Award worked very well. It achieved the goals of generating public discussion and providing publicity for the entrants.

Lessons learned

- The state government was serious about seeking innovative and deliverable design proposals from the profession, and thus decided to pursue a ‘design competition’ rather than an ‘ideas competition’. Funding, however, had not been secured for the project. Putting together the level of documentation requested required a significant amount of work, and at times entrants were not sure how much detail to provide given that it was a design competition.

- Ideally, at the commencement of any design competition, it is important to have clear messaging regarding the vision and purpose of the competition and how the project will proceed – for example, whether the project has or is likely to have funding. This allows consistent messaging to be provided throughout and provides clarity for the entrants. It also assists in managing the expectations of the entrants and the wider public.

- The competition was conducted over two stages during a period of approximately 13 months. Following the first stage announcement, there was a six-month mid-competition period prior to the commencement of second stage. This mid-competition period could have been reduced. A lengthy gap between stages requires ongoing management of resources for both organisers and competition teams to ensure that all the resources required are still available when the second stage commences. It also means that parties need to re-group and re-familiarise themselves with the project, a task which requires time and can add further complexity for joint ventures.

- The prize money for this competition was not significant based on the scale of the project and expected submission detail. A larger fee would ensure that each competitor would be able to cover a greater proportion of their participation costs. Allowing for flexibility in the competition conditions in relation to the distribution of prize money is important.

- Ideally, in such a significant competition, the architect of the winning design would be engaged as the project architect and, based on the rigor of the process, this appointment should be apolitical, transcending any change in government.

Competition case study 2

Project name: Frankston Station Design Competition

Winning Architect: Genton

Competition Type: Open Project - Two stage

Year: 2016-2017

Location: Frankston, Victoria

Client: Transport for Victoria (TfV)

Endorsement: Australian Institute of Architects and the Australian Institute of Landscape Architects Guidelines for the promotion and conduct of competitions

Project budget: $22–25 million (estimated direct construction costs)

Process

Rebuilding Frankston Station was identified as the flagship project of the Victorian Government’s $63 million investment in the redevelopment of the Frankston Station precinct. The value of a design competition in conveying the importance and value of a well-designed station was understood by TfV, who worked with OVGA to develop a competition.

Led by a competition adviser, a two-stage process was developed in response to the particular project needs and timelines. A brief and competition conditions were developed and agreed between agencies.

The call out for stage one entries was made internationally, with 40 entries received. These ideas-based entries were shortlisted to five through an anonymous judging process.

To begin stage two of the competition, the five shortlisted teams were taken to site and briefed by the competition organisers, the jury, the local council and rail operators.

Halfway through stage two, entrants were required to lodge their 50 per cent designs, which enabled a cost planner and technical review panel to provide feedback on the developing designs, which informed the final entries. A capability assessment was also carried out during stage two, where competition teams were given guidance in addressing the required capability criteria, to ensure project teams possessed the capability to complete a project of this scale.

Outcome

The winning design was unanimously agreed by the jury in March 2017 and announced by the Minister for Public Transport soon after. The winning architect was then engaged by the client to progress their design at the conclusion of the competition, with construction due to commence in early 2018.

Key Initiatives to protect design quality

- The two-stage competition process was designed to open up eligibility beyond the usual firms typically considered for rail projects, to invite fresh thinking and skill up more design practices at a time when the state is investing heavily in transport infrastructure. A broad variety of firms were shortlisted.

- The stage one format allowed projects to be assessed on the merit of their design ideas and did not limit the scope of entries, attracting wide industry interest and ideas.

- An exhibition of stage one entries and national media coverage raised the profile of the project across the community and profession.

- Stage two was designed specifically to respond to the requirements and tight timelines of the project, building in a successful feedback loop to allow the designs to progress quickly in an informed way. Review and advice on the designs was provided both midway and at completion of the stage two process by rail experts within state government. This technical input during the sketch design process gave the client assurance that the designs being considered by the jury would be informed, buildable and comply with the many standards and requirements specific to a rail environment.

- Payment of $40,000 to each of the shortlisted teams for their work in stage two was important to acknowledge the value of the work produced.

- Employing a dedicated competition adviser to prepare and manage the process was invaluable. The competition adviser brought experience in the preparation and technicalities of various types of competitions along with knowledge about working with a range of stakeholders.

- The competition adviser ensured the cultivation of a strong jury culture, which along with a well-prepared process, ensured the jury was well-informed and worked very well together.

- A good relationship between agencies, supported by a memorandum of understanding and dedicated resources at both ends of the project, enabled the process to move fast, with quick turnaround and responses.

- Community feedback was gathered and provided in a report to the Jury.

- Strong support and buy-in across state and local government as well as departments and agencies ensured everyone involved was on board early to work positively towards the same goal.

- The jury was carefully selected for a diverse mix of skills, experience and gender, bringing a fresh, intelligent and varied perspective to the process. Having a number of stakeholder representatives on the jury ensured buy in for the process, and enabled cross-agency agreements to be brokered during the judging phase.

- Representation from the Office of the Victorian Government Architect signalled the importance and value that government was placing on design quality.

Lessons learned

- Due to political commitments, timelines for project delivery were tight and therefore the competition timelines were also tight, allowing limited space for flexibility.

- Building in more time for technical and budget feedback during stage two would have been beneficial, enabling a more comprehensive feedback loop between technical advisers and design teams.

- Information provided on the budget, procurement method and construction timelines, was necessarily vague in the stage one briefing material, as these aspects were not resolved at the time. A longer timeframe would have been beneficial to address this issue.

- Timetabling the lodgement of entries to allow time before the presentation to jury was a wise move. Requiring stage two design concepts to be delivered two weeks ahead of the presentation date ensured design teams were fresh and practiced on the day.

Competition case study 3

Project name: Shepparton Art Museum (SAM)

Winning designers: Denton Corker Marshall Architects

Competition Type: Limited Select

Project Year: 2016–17

Location: Shepparton, Victoria Client: Greater Shepparton City Council and Shepparton Art Museum Foundation

Endorsement: Australian Institute of Architects

Project budget: $22–25 million (estimated direct construction costs)

Process

The Shepparton Art Museum Concept Design Competition was for a new building for the Shepparton Art Museum (SAM). The aim of the competition was to identify an architectural team and concept design for an outstanding example of exciting, innovative, best-practice contemporary museum architecture.

The project was funded by the Greater Shepparton City Council, the State Government of Victoria and the Commonwealth Government, which each committed $10 million, and the SAM foundation which raised $4.5 million. The project budget was $34.5 million, with a total construction budget of $22 million. The winner was announced in April 2017.

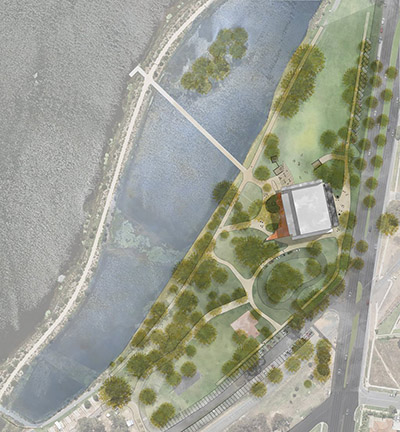

The competition for SAM was seeking a design concept that captured the benefits of the impressive Victoria Park Lake site and one that offered an engaging museum space that would welcome diverse communities, show collections to advantage and facilitate a range of curatorial approaches and art practices.

The Greater Shepparton City Council, as project sponsor, managed the process through establishing an Organising Committee and appointing a professional design competition adviser, procurement coordinator and probity adviser. The competition process was endorsed by the Australian Institute of Architects, and competition eligibility was limited to architects, or teams led by an architect, registered to practice in Victoria or with the capacity to be registered.

The jury comprised seven members as a skills-based jury, with professional members drawn from the arts, architecture/design, academia, Indigenous architecture and related industries. The Office of the Victorian Government Architect was represented on the jury. The jury assessed both stages of the competition through a rigorous, iterative process.

The competition was a two-stage process. The first stage was an expression of interest where entrants were asked to provide one A4 document of no more than five pages that detailed a statement of the design team’s design approach and the capability and experience of the team. Stage one received 88 entries. The calibre was high, with many entries from architectural teams capable of delivering a very high-quality art museum. The jury undertook multiple rounds of assessment of this very competitive field, and selected five teams to proceed to stage two. The teams, were Denton Corker Marshall, John Wardle Architects, Kerstin Thompson Architects, Lyons Architects, and Minifie van Schaik.

The second stage, concept design stage, required the shortlisted proponents to develop their initial concept design based on the concept design competition brief. Each of the shortlisted teams received an honorarium to assist them in preparing their final design entry. The five entries were assessed against criteria.

Outcome

The design competition was won by Denton Corker Marshall in collaboration with landscape architect Bruce Eckberg of Urban Initiatives, ARUP engineering and Wilde and Woollard Quantity Surveyors.

The competition involved a two-envelope process to determine the acceptability of the fee. After a decision was made as to the non-financial aspects of the entries, the second envelopes were opened by representatives of the Greater Shepparton City Council. The Denton Corker Marshall team fee proposal was within the pre-approved range.

The five shortlisted designs for the New Shepparton Art Museum were on display at the Eastbank Centre in Shepparton from 16 January 2017 to 5 February 2017. Members of the community were encouraged to view the exhibition and provide feedback on the concept designs. There was much interest from the community, with 1,417 feedback forms completed either online or in hard copy. Overall the feedback was incredibly well thought out and constructive, with only 20 negative responses. The community voted for all five designs with particular interest supporting three of the designs. The comments and feedback were discussed and taken into account by the jury during their deliberations.

Key Initiatives to protect design quality

- The competition sponsor ensured that the competition conditions allowed entrants to retain their intellectual property and moral rights in their designs.

- A detailed and visually compelling competition brief included well-considered evaluation criteria.

- A detailed set of competition conditions provided entrants with confidence in the process and outcome.

- The client retained a commitment to the design quality and intent of the project and the process.

- The competition had a design competition adviser and jury chair who were highly capable.

- The competition encouraged concise and targeted entries from entrants.

- Representation from the Office of the Victorian Government Architect signalled the importance and value that government was placing on design quality.

- The Australian Institute of Architects endorsed the competition guidelines, and a design competition adviser was appointed. The client followed recommended and endorsed design competition processes with which all designers were familiar.

- The process included shortlisting and provision of payments to each of the five shortlisted entrants.

- The use of oral presentations assisted in focusing the selection process, and identifying the design teams’ capacity to work with client and stakeholders.

- The strong governance structure meant that each group had defined roles and responsibilities.

- There was a high level of public engagement and extensive feedback.

Lessons learned

- Regional areas should be prioritised by government when it comes to providing design support, as often local government lacks the resources and design capability to run competitions effectively. In this case, the right steps and governance were in place to ensure a successful outcome and a highly considered jury process.

- The prize money for this competition was $10,000 for the winner and an honorarium of $7,000 for all entrants in the concept design stage. This sum was not reflective of the time and resources expended by the design teams.

- Allow enough time for the jury to bond and be familiar with the expertise and background of each individual.

- At the commencement of any design competition, it is important to be clear that the project has funding. This allows consistent messaging to be provided throughout and provides clarity for the entrants. It also assists in managing the expectations of the entrants and the wider public.

- The competition was conducted over two stages within a period of approximately seven months. This was an appropriate length of time to capture the best response from entrants and keep the project fresh in the mind of the jury.

Competitions may not be the only method of career advancement for an architect, but no award in the profession – with the exception of the Pritzker – quite matches the stamp of approval conferred by winning a major design competition.

References

1 Flinders Street Station Design Competition: design brief, Major Projects Victoria, State Government of Victoria

2 Flinders Street Station Design Competition: jury report, Major Projects Victoria, State Government of Victoria

Guidelines for the conduct of architectural competitions, Australian Institute of Architects, February 2016

Model conditions for an architectural competition, Australian Institute of Architects, February 2016

Architectural competitions policy, Australian Institute of Architects, April 2015

Architectural design competitions: how when and why to commission them, Integrated Design Commission of South Australia, Andrew Mackenzie

Government as ‘smart client’, Office of the Victorian Government Architect, 2013

Competitive design policy, City of Sydney 2013

Design competitions, Office for Design and Architecture South Australia, Design Guidance Note August 2014

Updated